Management of the most valuable (Time)

It’s pretty safe to say that time management is the ultimate over-arching skill that penetrates every endeavour one is trying to reach. Everything requires time, and managing that time will automatically give you a default starting advantage over anything you’re trying to achieve.

I would like to start-off by saying, that the thing that took me the most time to figure out (and still does), is identifying the order/sequence of “doing” and “planning”. Like what comes first, does or should planning precede action, or does/should action sometimes come first, and shape the plan along the way ? and the answer is really not obvious when you look at the uncertainty and ever-changing conditions of life.

It’s not obvious to me how relevant this question is to time management, but it seems like time management is fundamentally a dynamic between plans and actions, in the background of the finiteness or limit of a human being’s time.

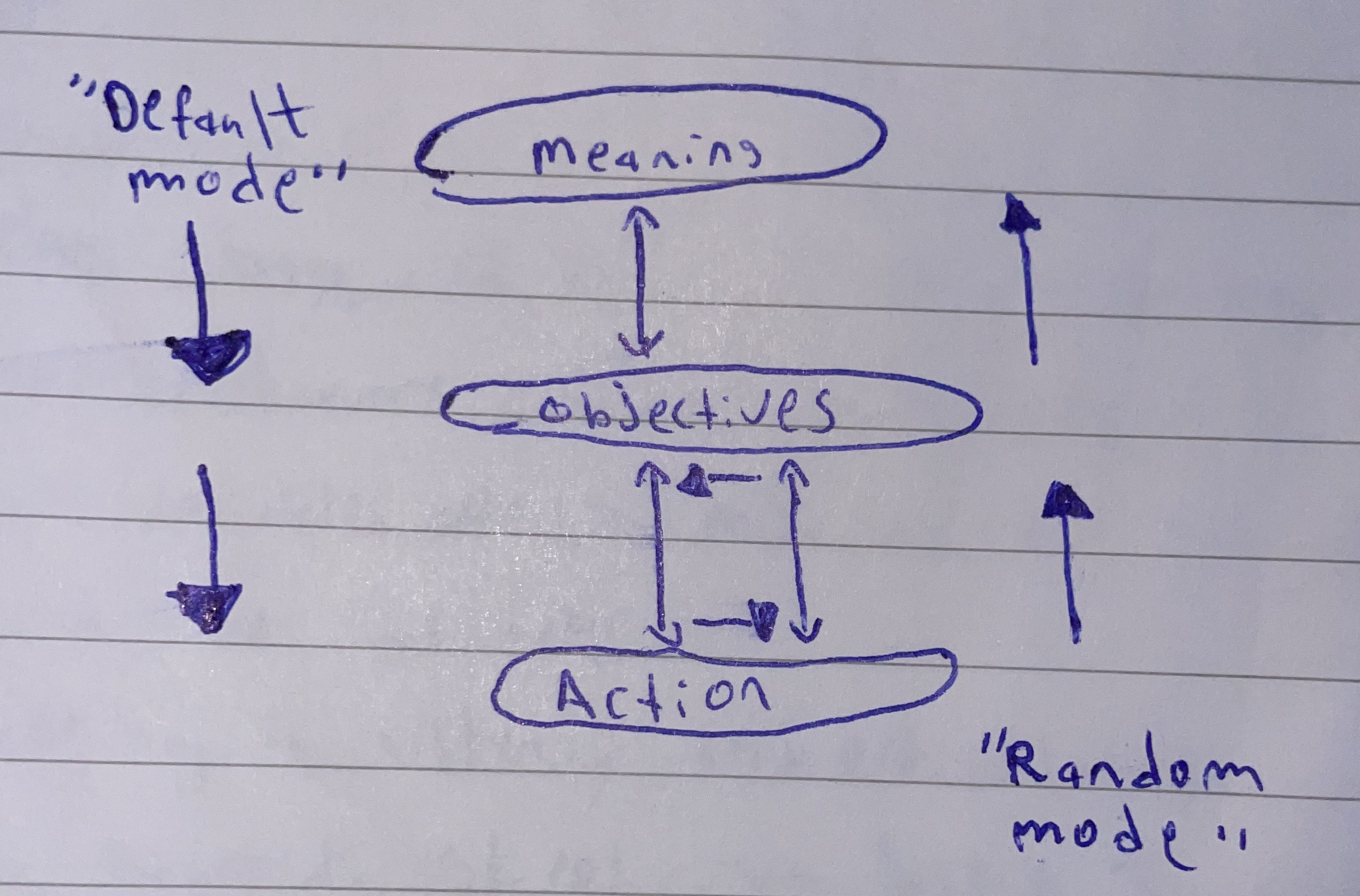

So let’s begin by trying to answer the question, and I’ll start-off with an illustration I drew that will make things much easier to understand throughout the answer:

Building the model from scratch:

The first thing to establish is that this framework is really a general description on how we act, rather than how it should be in every context. Obviously, this semi-informs how things should be in some regard, but it’s not at all exhaustive.

Now, let’s break it up, what I mean by meaning is really the vague general master plan we have towards the approach to different things in life. That is not to say that it’s explicit and clear in everything we do, but we usually have some meaning or purpose that informs our objectives and actions, at least when we do things rationally, which, I believe, is not always the case.

An example of that would be when people go to university, or when one starts a business, one purpose or meaning is to provide a descent life financially (along with other meanings, of course), without reference to any specific details on how that’s going to get done.

Now the second pillar we had was the objectives part, which is informed by the meaning, but objectives are usually more specific or practical. We saw in the previous example that meaning/purpose is to have a financial backing, for instance, now, the objective would be how you come to do that through. Are you going to be an accountant through going to university, an artist, an academic, or a freelancer. Some kind of specific Plan generation usually happens at this stage.

Before moving on to the action, note that a purpose doesn’t require you to have an extensive plan, initially, the meaning might even be a mere intuition, but the objectives stage is usually when one sets a plan. And this fact tells us that as one progresses with a plan and is trying to fulfill a bunch of other meanings as well, “objectives” can decouple from the “meaning” sometimes, which is an interesting time management side note we can think about.

The third pillar would be action phase, which is usually the time when one implements all the ideas they had in mind.

As we see in the illustration, there is a constant feedback between the objectives and actions, and that’s due to the uncertainty of life and flaws in our expectations. One might set objectives, but as soon as one starts acting, they change x, y, etc. in their objectives.

If we localize where the time management argument fits in this paradigm, we see that the time management problem emerges somewhere between the objectives-actions phase.

What I will say before moving on, is that this whole process is not necessarily conscious. A lot of the times people actually extract their meaning from conventional societal norms (or some other reason) without consciously going through it, which is, interestingly enough, one of the functions of society, because one simply doesn’t have enough wisdom, at least initially.

So approaching the problem of time management while keeping in mind our localization and diagnosis through the model, is key when trying to solve the problem, because it accounts for all the clear variables in the playfield, as far as we can see them, at least.

Like all models, the descriptions we talked about above doesn’t fully describe all approaches we have towards achieving things.

So to extract every insight we could from our flawed model, reversing it and observing what explanation can come out (as we see in the illustration) is one way to understand how we approach the world even more.

“random” mode:

So random mode is really applicable when life presents an opportunity all of a sudden sometimes, the action happens and then planning is shaped while the action is being done.

In that case, our regular meaning-objective-action model is not really accurate, and it becomes quite disorganized, for lack of a better word.

In a practical case of “random mode”, if one keeps working without having some idea of the meaning/purpose or without objectives eventually, it might work for some while, and perhaps it’s needed for exploiting sudden opportunities that life gives us sometimes, but it will probably end up translating to burn-out from that action (or translate to other psychological forms), if the other two elements don’t eventually show up.

It’s worth mentioning one more thing, which is that going by and accepting the disorder of “random mode” is less true for some people than others, because it depends on temperaments and metrics of personality, things like openness to experience and risk-averseness.

Linking it back to time management:

Having mentioned all of this framework, I think that before setting any rules for time management, it’s good to be cognizant of all the things we mentioned, to have some kind of consciousness towards the different variables that weigh into this kind of calculation of time management.

Now that we have some insights on the background of our actions and endeavours, it would be good to mention a few principles that can make us optimize for “time management”, in light of this foundation.

#1: Plan in short-term segments, first.

So we said that after you have your meaning settled, objectives and planning come next. And this principle here is really related to the objectives part and how to approach it.

I think that, initially, planning in short-term segments is really optimal for translating plans into action. Let’s try to think about why that might be the case:

- When you plan in shorter segments (daily/weekly), you have less chance of an on-going unnecessary change of plans that can slow you down, because the further a goal is across time(ex.monthly/yearly), the less accurate your prediction to achieve it will probably be (at least initially), and the less the accuracy, the more unnecessary change in plans, which makes it more difficult to execute the plan consistently and psychologically.

So if we take an example of learning a programming language, if I say that I’ll work on problems in that programming language for 2 hours everyday, then there is a low chance of me bailing out of that commitment (assuming I have a well-established meaning, etc.) because it’s crystal clear and is very much a psychologically achievable goal.

However, if I say I’ll master learning the programming language at the end of the month (long-term goal), then the “unnecessary change” will haunt me, for the reasons we mentioned previously, and that approach of a “misplan” and unneeded change over and over again, will lead to different cascade events that will affect “time management”, and getting things done.

- Another reason why it’s more benign to plan more proximally, which we alluded to, is because the daily/short-term plans seem more psychologically achievable for a person than the monthly ones, for example, and that thing itself will cause the person to get on the task more, rather than procrastinate it or leave it all-together because it seems so heavy or psychologically daunting.

Now all of that is not to say that one’s plans should always be short-ranged, and with no deadlines, but what I am saying is that starting off with a short-term plan and then understanding the closely-related variables more, and afterwards, moving on to plan on a long-term is much more plausible to build a better sustainable framework of getting things done.

It’s a more achievable mission to have a bottom-up approach rather than a top-down approach, which means that, starting to understand all the close-range variables and plans, and then moving on to more distal or farther away plans is a rational and practical position to take from a time management perspective (keep in mind the out-of-norm “random mode” we mentioned, as these things we mentioned don’t always apply in every context).

#2: Set “x” amounts of introspective problems to solve every week:

This one seems completely out of the blue, I mean we already solve problems everyday by default, however, the part I am stressing here is really the conscious effort of identifying a certain amount of personal/introspective problems to solve every week.

The reason being that this attitude of picking things you want to change, will allow you to catch the small “sneak-in” problems that snowball themselves into obstacles, without being noticed.

You’ll be surprised how many issues/problems go unchecked and affect the “efficiency” of achieving, without us noticing them. And the principle we proposed will, on a long enough frame, allow you to gradually remove things that have this feature.

And the reason why I say introspective is to stress that this doesn’t mean that they should be difficult or hard-to-solve problems, I am really talking about even the small things like waking up as soon as the alarm rings, or less breaks during exercise, for instance.

Another thing that this approach will definitely allow for, is it’ll build a feedback loop between you and your weaknesses, if that makes sense, because if you keep identifying problems (which is the first possible area of weakness because it’s a somehow a skill), and then solve them, or try, at least,(which is the second possible area of weakness), you’ll have an existence proof on where you’re weaknesses lie, constantly.

Obviously, solutions to those problems will not always work out from the first trial, but whether the thing is solved or not, the process will probably teach you somethings about yourself in relationship to time management, and other domains of life as well.

#3: Think realistically not symbolically:

Before we explain the principle here, I want to stress that thinking in symbols, or thinking symbolically, is really a wide topic that is discussed in rationality and psychology circles, and it’s not necessarily an “incorrect” way to think in every context, and is sometimes seen as an integral part of how we think and try to make sense of things as humans.

Without delving into symbolic thinking and defining it extensively, let’s start by taking an example of the scenario that comes to my mind when I think about this principle:

in the context of time management: if we imagine a person who works, and studies in university at the same time, thinking “symbolically” would be equivalent to something like this: “I don’t really have time to work on ‘x’ or ‘y’, because I am juggling between those two main things.”

So the symbol here is: “I Work and study at the same time.”

And the idea of a symbol can be stretched out by the person to irrelevant situations, and might repress other side things one might’ve wanted to do, whether consciously or subconsciously.

On the other hand, the realistic approach here would be something like:

“Calculating how many hours I have during the week and objectively seeing how much time each task takes.”

Or

“Whether the workload/studyload changes during the week so I can work on other things.”

Or

“What habits can I change to gain more time for my other tasks, maybe I need to wake up earlier and finish up the side work, etc.”

Conclusion:

At this point, we have built a somehow relevant intuition, and proposed some principles, and to put the cherry on the top, so to speak, let’s move on to a conclusive reminder that, as simple as it seems, was quite enlightening to me when thinking about this framework, and that is the fact that the week has almost 118 awake hours. So our most valuable asset is quite generous, if we approach it with a mindset that gives its real value.