Knowledge and information; The difference

If you start by asking yourself the question, what is the difference between Knowledge and information?

you would probably struggle in finding an articulate, meaningful answer.

And aside from the fact that each word has interesting things to think about when it comes to its definition,

These two concepts are actually different in very interesting and practical ways.

And in this digital age we are living in, where humans are being more and more approximated to computers, and brains are being approximated to silicon chips & Computer processing units,

it seems like this distinction is becoming more of an elephant in the room that needs to be addressed.

So before we spree into the difference between the two from our perspective, it’s always good to actually go back to the history of why the question of the difference between them, fundamentally emerged,

because it’ll give us one of the deepest applications of the idea, which is from where it emerged.

The line being drawn:

Interestingly, it was the Austrian Economics School of thought,

that actually elaborated on the difference between the two, in a discussion about prices and markets.

So in the beginning of 1900’s, there was a big discussion revolving around how a socialist society would actually allocate/calculate its resources, without constant prices feedback (That’s because Socialists believed in the idea of “shared resources”, with no price-tags).

And the idea was that non-socialist markets (Which is what the Austrian Economists supported) have different people in the market, setting prices in an organic, constant, & contextual evaluation and feedback, between buyers and sellers, which allowed for real-time feedback, for the wise allocation of resources in an Economy,

as opposed to a “Socialist” society, which would have all these “organic”, contextual emergences & feedbacks, curtailed or removed all together.

So that begged the question for the Austrian Economists, of how a Socialist society would allocate resources in an efficient, or even a realistic way.

And one of the main summarised conclusions that the Austrians put forward to that question (spearheaded by mostly Fredrick Hayek, & also Ludwig Von Mises), was phenomenal to say the least, not just to the field, but even extrapolating it to different human approaches like epistemology (Theory of knowledge), and theory of mind.

They ended up standing behind the belief that a Socialist society can’t possibly efficiently allocate and deal with finite resources reasonably, through an exclusive central planner (which is mostly the case in a socialist context), because in the intricacies of the real world, “information” about those resources, and where they should go, is not some recipe the central planner has, or a recipe sitting there waiting to be found or discovered by a central planner,

but it is/has to be constantly invented and modified by economic actors, in specific private dispersed contexts, interacting in the market.

So from that point/discussion on, there ideas have started to crystallize more regarding our very interesting distinction, which we’ll take a stroll in discovering.

Information is overrated; Knowledge is underrated:

Now, I would actually start by saying that this title would sound so weird and ungrateful, if it was in another time before the digital age, because information was just so scarce to attain in the days of old,

however, we, in this day and age, have virtually reversed the problem completely, and made information infinite in the matter of a century (which absolutely blows my mind everytime I think about it).

So in the presence of infinite information, it’s so crucial to set the boundaries on how far it can actually go into the individual human psyche/condition.

Which makes the distinction between it, and knowledge relevant now more than ever.

And although they’re overlapping a lot of the times, but they’re also different in interesting ways.

So if we start by setting the stage for information, we can describe it as the conveyable or even a transferrable piece of data or communication.

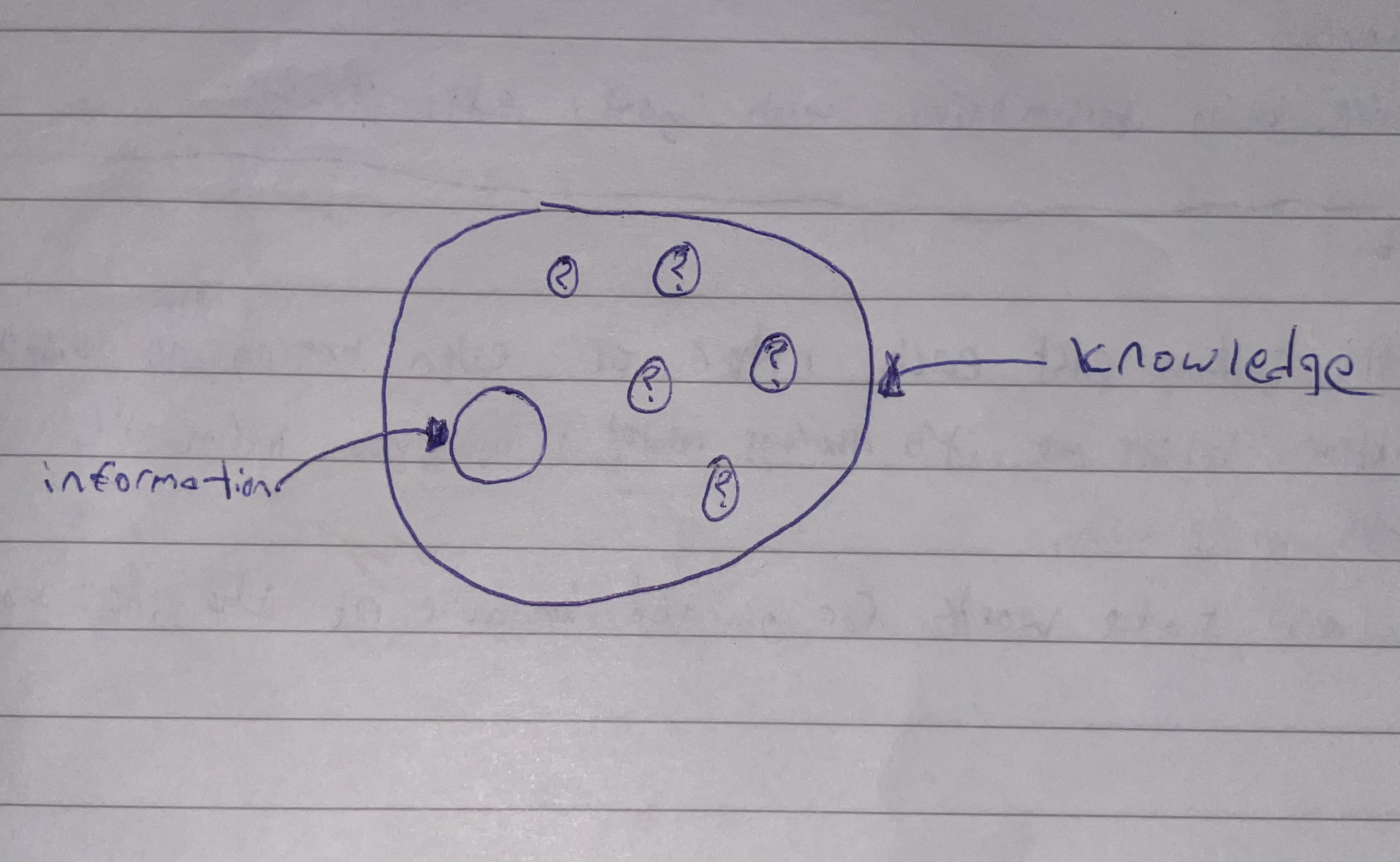

So you can think of information being a “flow” to the bucket of the human mind (whether collective human mind or individual), let’s say.

The Austrian thinkers, whom we spoke about earlier, would also add that it’s the raw data, that’s perhaps closer to being the “objective” type of communication.

Now, you could argue that everything that’s effectively in the human mind, is actually information (which is the approach some academics have), so the “bucket” is only an aggregate of the “flow”, that’s all it is, so let’s stop here, Thamir,

But that’s ignoring a lot of the constituents in the complexity of the human mind, and also the inherent uncertainty of the world.

Which is where knowledge comes in and further rectifies the situation.

If information is the thing that flows, knowledge is the aggregate of what’s in the bucket, where the bucket has all sorts of complex variables that transcend information, which we’ll unpack.

Knowledge, on top of “information”,( as we described it) being a part of its whole,

is also the acquintance of real-life conditions/situations that can’t and usually isn’t conveyed or transferred.

You can think of it as the very contextual/private type of acquaintance (partly subjective, is also one part you can describe it as).

So people in law school or medical school would receive a lot of “information”, but they don’t actually complete the circle of “knowledge”, until they deal with the different variations, and uncertainties of the real world, that are highly contextual and private, and can’t be passed on, or even replicated.

Now when I say contextual, I don’t only mean external factors like the specific situation, but I also mean internal factors, like personality traits, for instance.

An extroverted judge will simply change the “context” of the trial, not because of an institutional, or any other external factor, per se, but because of that personality inclination.

You can also build that idea on the lawyer’s personality and how to deal with that, the jury, and all other people in the court room, which make our point of contextual knowledge, and also “information” being only a part of the grand scheme, even more obvious.

Another angle to look at this distinction, and actually prove it at the same time, is that: when you give two different people the same exact “information”, they simply receive and act on that information very differently.

which goes to show that their “knowledge” inventory, and whatever it gives rise to, is simply different, and that’s why they use the same “information”, differently.

Another big part of knowledge, is that it sometimes emerges on the spot, in that specific/private context, and that’s why it can’t really be transferred, and also excluded from something we would call “information”, explicitly,

Which can be described as what we call human creativity.

It’s also interesting to think about the fact that the parts of the human mind that are related to “information”, as we loosely defined it, are actually more scientifically understood (though still much more to be explored), where the parts related to “knowledge” and “creativity” are the least explored/understood.

Now, I do want to stress that I don’t want it to come across like I’m detaching the two from each other,

because both of them are actually informed by each other,

And we mentioned previously, they’re both overlapping in many ways, but also dissimilar in many other different interesting ways we discussed.

Truthful or Useful?:

Now I want to say that, you could virtually be rigorous about this, and argue that the two concepts are actually, fundamentally the same.

Sure, you could say that, we can agree to disagree, but I would actually posit that the distinction is actually pretty useful more so than it’s absolutely and completely truthful, let’s say.

It’s useful in the sense that looking at this model/distinction, and applying to a learning experience, would translate into an approach of trying to constantly transfer the “information” you receive, and constantly integrating it into the deeper “knowledge” base by applying that information in different contexts, let’s say.

So If I want to become a lawyer, even if I have the “information”, there is a certain threshold that I can’t pass, until I actually apply it in a real-world context of working in a real court, and convert it into “knowledge” that I can deal with in different contexts, for lack of a better word, or building my own inventory of creativity in the field.

And I’m aware that this is common knowledge, to some extent, but you’ll be surprised how much we forget it in certain aspects of our lives.

clearly, in a career it’s obvious that everyone will eventually translate the information into knowledge, but a lot of the times we forget it, in other domains of life.

Novelty vs Repetition:

This seems a bit off-topic, but the link will become clearer once we inspect it deeper.

So exploring/thinking about Novel/new ideas usually gets a lot more credit, than ,say, repeating/thinking about the same idea again and again. Which is great, not a bad thing at all.

But repeating already known ideas in many different ways, thinking about them from many different angles, also, (perhaps equally so) gives rise to new insights, constantly.

because it might actually speak to some of the knowledge inventory that’s in our subconscious mind, which we also have to constantly keep discovering, for instance.

We often assume that new answers lie outside of ourselves, in some deep way, and although that’s partially true, but the conversion of knowledge, also requires an internal thought process of repeating the ideas we already have, in different ways.

Here is how I like to think about it:

New Information will be directed to our conscious mind, and milking the more “active” consciousness.

Repetition is redirecting the attention, in one way, to the subconscious, and the knowledge inventory of the human (which as we said, can be subconscious, a lot of the times).

Finding the balance between those two in a plainfield of disorder & complexity of the human’s learning process, is underrated gem.

Conclusion:

Since we started this piece with the Austrian Economists, let’s also end it on one of the wisdoms they shared once, on the state of equilibrium in markets,

which can actually implicitly summarise our discussion, beautifully:

Equilibrium in the market is not some “level” to reach, but it keeps reinventing itself because it’s agent & time-dependent. Whenever we know someone is doing something, we change actions accordingly, regardless of the “information” we have, and a new “equilibrium” baseline is invented on spot, scale that up on markets, and you’ll see how knowledge is a more precise framework to think about the world, and how to act in it.

We can end on this meta-note, by saying:

learning is the process of properly mixing information into our complex knowledge inventory, that better “knows” how to deal with uncertainty of the complex world and its situations.

and recognizing that in this age of “information” is crucial for us to actually, and perhaps more precisely and productively, turn it into the “age of knowledge”.